Or are you the sort who'd rather imagine yourself moving to the swish of heavy Georgian silk?

Or... if you picture yourself as the smart, independent-minded woman you (or I) surely would have been 100 yea

rs ago, you might well see yourself in a shirtwaist and simple, straight dark skirt.

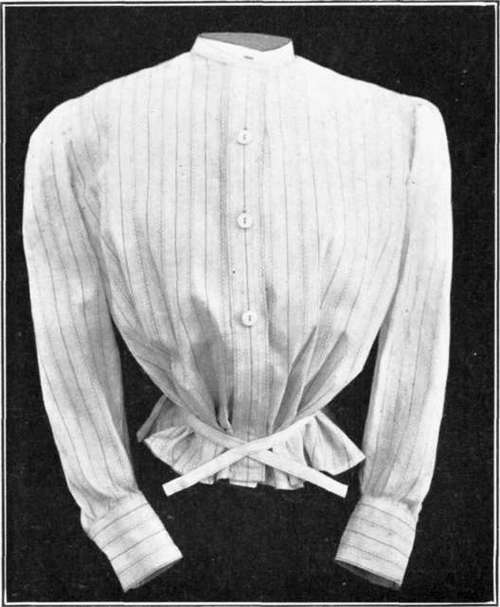

rs ago, you might well see yourself in a shirtwaist and simple, straight dark skirt."Waist" was the word for blouse then, and though some of them were frilly, Gibson Girl concoctions like the ones to the left, others were simpler affairs, like the one below...

...which perhaps, if you were a recent immigrant to this country like my grandmothers in, say 1910, you might have worn to work at one of the 450 factories in New York City that made shirtwaists.

The look was wildly popular; the demand helped New York City become a fashion and garment-manufacturing mecca, and the style became a hallmark of young women who didn't have to depend upon a man (or not quite yet, anyway) for their subsistence. Or as my friend Jeff Weinstein put it last week in a wonderful blog post, shirtwaists were "turn-of-the-century blouses that had modernity written all over them, the free woman's uniform -- even if she couldn't vote."

"Think of them," Jeff urges, "as cotton Nikes." Both because of the freedom both products promise, and, he adds insightfully, because "in both cases it's been convenient to forget who makes them."

But this week, on this history lovers' blog, I hope we don't forget who made the shirtwaists, and the Nikes, and so much of the clothing we love, both from now and from then. Because last Friday was the hundredth anniversary of the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire, when 146 workers, mostly girls and women like those in the picture below, died because the factory owners couldn't be bothered to provide the most minimal safety standards.

And after you read more about them in Jeff's superb longer piece here, (having been sure to check out the rest of the photographs he provides), remember as well that the exquisite muslins and dimities of Regency England came from Manchester, where in 1819, almost 100 years before the Triangle fire, a peaceful demonstration largely of mill-workers was attacked by the Manchester Yeomanry.

The rout is portrayed in this Cruikshank cartoon, which I got from Wikipedia

, where I learned that of the 684 reported dead or wounded at what became known as the Peterloo Massacre, "...at least 168 were women, four of whom died either at St Peter's Field or later as a result of their wounds," and that "it has been estimated that less than 12% of the crowd was made up of females, suggesting that women were at significantly greater risk of injury than men by a factor of almost 3:1."

, where I learned that of the 684 reported dead or wounded at what became known as the Peterloo Massacre, "...at least 168 were women, four of whom died either at St Peter's Field or later as a result of their wounds," and that "it has been estimated that less than 12% of the crowd was made up of females, suggesting that women were at significantly greater risk of injury than men by a factor of almost 3:1."And where I also learned that at least part of that 12% represented "female reform societies... formed in northwest England during June and July 1819, the first in Britain" and that "many of them were dressed distinctively in white, and some formed all-female contingents, carrying their own flags."

I wish I could remember where I read that many of them also wore greenery in their hats, which detail I find overwhelmingly moving, and which probably had something to do with the title I gave this post, about the idealism and lyricism woven into these struggles, most beautifully captured in the poem, "Bread and Roses," soon to be a song, by James Oppenheim, published in 1911, a few months after the Triangle Fire, and associated with the successful strike in the textile mills of Lawrence, Massachusetts, and sung by a contingent of women workers:

(You can hear it sung here as you read it)

As we go marching, marching, in the beauty of the day,

A million darkened kitchens, a thousand mill lofts gray,

Are touched with all the radiance that a sudden sun discloses,

For the people hear us singing: Bread and Roses! Bread and Roses!

As we go marching, marching, we battle too for men,

For they are women's children, and we mother them again.

Our lives shall not be sweated from birth until life closes;

Hearts starve as well as bodies; give us bread, but give us roses.

As we go marching, marching, unnumbered women dead

Go crying through our singing their ancient call for bread.

Small art and love and beauty their drudging spirits knew.

Yes, it is bread we fight for, but we fight for roses too.

As we go marching, marching, we bring the greater days,

The rising of the women means the rising of the race.

No more the drudge and idler, ten that toil where one reposes,

But a sharing of life's glories: Bread and roses, bread and roses.

Our lives shall not be sweated from birth until life closes;

Hearts starve as well as bodies; bread and roses, bread and roses.

No comments:

Post a Comment