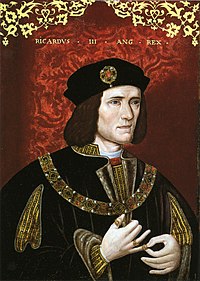

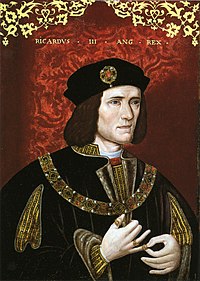

I never noticed that this portrait does show one shoulder slightly higher than the other ... but I believe it's the wrong shoulder!

I never noticed that this portrait does show one shoulder slightly higher than the other ... but I believe it's the wrong shoulder!

I don't know about you, but my introduction to Richard III and the Wars of the Roses, perpetuated for decades by the feuding dynasties of Lancaster and York, was through William Shakespeare. I was in high school at the time, and it would be years before I learned that the man rarely let the truth get in the way of a good story.

Now that historical research is part of my bailiwick, I'm having great fun re-reading Shakespeare's history plays and separating the factual details from the fanciful ones.

As I've been delving into Richard's life for my third work of historical nonfiction, currently titled

ROYAL PAINS: A Rogues' Gallery of Brats, Bastards, and Bad Seeds, I thought it would be fun to revisit Shakespeare's text after having a "eureka!" moment during my research into Richard's actual, factual, life.

Richard had a happy marriage.Who knew?

Consequently, Richard and Anne Neville didn't make it into my post some months ago about happy marriages in Shakespeare; but today they get their due.

And by the way, Richard was also not born with a crookback, or a withered arm. Or a full set of teeth, or shoulder-length hair. Nor did he gestate in his mother's womb for two years. These physical descriptions are the products of Tudor-era propaganda, most of which no rational person, at least in our day, would credit. And yet -- the humpback, and even the useless arm, have stuck with us, providing the image of a Yorkist Bob Dole (yes, I know Dole isn't

hunchbacked). The truth appears to be that Richard had one shoulder (the left one) that was slightly higher than the other, and that he was frail and slight as a boy, in stark contrast to his handsome brother George, Duke of Clarence, who was a charismatic jock-type, or his 6' 4" oldest brother, Edward IV, a ladykiller, bon vivant and fashionisto until job security after 1471 turned him into a louche and lascivious gourmand and womanizer.

Richard did indeed have to push himself to overcome his frailness as a boy in order to excel in the usual manly pursuits of the era from martial skills to horsemanship, falconry, riding, and dancing. He

did in fact know how to "caper nimbly in a lady's chamber to the lascivious pleasing of a lute."

But back to Richard's marriage.

In Act I sc. ii of Shakespeare's

Richard III, our protagonist, then Richard Duke of Gloucester, woos the widowed Anne Neville in exceedingly reptilian fashion. The encounter takes place on a London street in the middle of a funeral cortege. Anne was the younger daughter of Richard Neville, 16th Earl of Warwick, known as "the kingmaker" for his Karl Rove-like strategic (and martial) talents in securing England's throne for the Yorkist usurper Edward IV, then backing the man Edward had deposed, the Lancastrian Henry VI. Anne's older sister Isabel had, against the wishes of King Edward IV, married George, Duke of Clarence, brother of Edward IV and Richard, Duke of Gloucester.

Anne Neville's father, Richard Neville, 16th Earl of Warwick, known as "the kingmaker" -- hardly a St. Francis-type. This drawing is from a chronicle of the time known as the Rous Roll.

Anne Neville's father, Richard Neville, 16th Earl of Warwick, known as "the kingmaker" -- hardly a St. Francis-type. This drawing is from a chronicle of the time known as the Rous Roll. In Shakespeare's wooing scene, Anne has recently lost her husband, Prince Edward (the former Prince of Wales), son of the deposed (and subsequently assassinated) Henry VI. Edward fell in the battle of Tewksbury on May 14, 1471, which decimated the Lancastrian forces, ushering in years of Yorkist supremacy.

Anne Neville: note her long red hair Throughout Richard III, the late Prince Edward is described as noble and virtuous. The real Edward of Lancaster was an arrogant 16-year-old jerk. He and Anne (b. June 11, 1456), who married him on December 13 1470 at the age of 14, had a purely dynastic marriage. And, contrary to Shakespeare's text, Richard (b. Oct. 2, 1452) did not personally stab him to death; During the battle Edward was in fact set upon in a melee. The identity of the man who delivered the fatal thrust remains unknown .In their famous scene in

Richard III, Anne is not lost for epithets to sling at her pursuer: "fiend," "dreadful minister of hell," "foul devil," "defused infection of a man," "devilish slave," "hedgehog," and "homicide." I think "defused infection of a man" is my personal favorite, though "hedgehog" comes in a close second. Richard's heraldic device was the boar, so maybe this is one of the ultimate inside jokes, a deliberately bitchy twisting that reduces a noble, if overbearing, creature to a woodland nuisance.

Here's a sample of Shakespeare's version of this highly unusual -- and exceedingly swift -- courtship:

GLOUCESTER: He that bereft thee, lady, of thy husband,Did it to help thee to a better husband.LADY ANNE: His better doth not breathe upon the earth.GLOUCESTER: He lives that loves thee better than he could.LADY ANNE: Name him.GLOUCESTER: Plantagenet.LADY ANNE: Why, that was he.GLOUCESTER: The selfsame name, but one of better nature.LADY ANNE: Where is he?GLOUCESTER Here.[She spitteth at him]Why dost thou spit at me?LADY ANNE: Would it were mortal poison, for thy sake!GLOUCESTER: Never came poison from so sweet a place.LADY ANNE: Never hung poison on a fouler toad.Out of my sight! thou dost infect my eyes.GLOUCESTER: Thine eyes, sweet lady, have infected mine.LADY ANNE: Would they were basilisks, to strike thee dead!

This spirited sparring comes from one of the finest, and most famous, scenes in Shakespeare's canon, and I can attest that it is also one of most fun to perform -- but it is pure fantasy.

England was more or less embroiled in civil war when Richard was a boy, thanks to the perpetually warring factions of Lancaster and York. He was sent out of harm's way to lodge with Warwick's family at Middleham, the earl's Yorkshire estate. Richard and Anne were childhood playmates, and as such, were always fond of each other.

In 1470, the reign of Richard's older brother Edward IV was being challenged by a conspiracy to reinstate Henry VI, fomented by none other than their own brother the Duke of Clarence (who had the dim and addlepated notion that

he would eventually be crowned) and the Earl of Warwick, Clarence's father-in-law, and the pestilence in his ear.

Richard, still in his late teens, headed to command and secure the north for his brother Edward, but before departing he requested, and was granted, permission to wed Lady Anne Neville. When he returned from the north to claim his bride, he discovered that Clarence, husband of Anne's sister Isabel Neville had decided that Anne was his ward (Warwick having been killed at the Battle of Barnet on Easter Sunday). Clarence intended to claim Anne's portion of her inheritance for himself and Isabel and therefore had no desire to see her wed, even to his own kid brother.

In fact, it is Clarence who is the villain of this particular portion of the story. He disingenuously insisted to a confused and angry Richard that Anne was not in his household. After an exhaustive search, Richard found his betrothed in London disguised as a kitchen maid in the home of one of Clarence's friends. Like a true romantic hero, he rescued her and brought her to sanctuary at St. Martin le Grand, thereby shielding her from any efforts by Clarence and his adherents to nab or harm her. He assured Anne that there were no strings attached to his chivalry; his action in no way obligated her to go ahead with their marriage.

Insisting that he was the girl's guardian following the death of her father, Clarence ultimately consented to permit Richard to wed Anne on the condition that Richard inherit none of her estates.

Anne and Richard were cousins; in order to legally wed they required a papal dispensation overlooking their consanguinity. But having finally secured permission from his family to marry Anne, Richard was too impatient to wait for the Pope's paperwork to arrive. Instead, on May 14, 1472, political expedience being as pressing as passion, he claimed his beloved from St. Martin le Grand and they were wed on the spot. The bride was one month shy of her 16th birthday. The groom was 19 (and he'd already fathered two children by then; I don't know the mother[s]' name[s].)

When was the last time you saw a production of

Richard III where the characters were played by actors young enough to look like teenagers?! I'm betting never.

The couple --who were genuinely in love, at least according to Richard's eminent twentieth-century biographer Paul Murray Kendall -- immediately set off for Wensleydale castle, far from any of their grasping relatives. They had only one child, a son named Edward born in 1473, whose health was always delicate and often prevented him from traveling with his parents. He was invested as Prince of Wales on September 8, 1483, but he died during the spring of 1484 at the age of 11. Richard and Anne were inconsolable, and it was said that the boy's death hastened her own demise.

Unlike Shakespeare's plot, in which Richard is ultimately suspected of poisoning Anne in order to wed his niece, Elizabeth of York, Anne developed consumption, the same disease that killed her older sister Isabel. Wasting away from grief and illness, she died on March 16, 1485, a little more than five months before Richard met the sharp end of a sword at Bosworth Field on August 22.

Richard still remains an enigma to us, a product of the violence of his times; a loyal brother and talented administrator, but unquestionably he had blood on his hands. In Shakespeare's "defense," he based his history play on the Tudor-era writing of chroniclers Edward Hall, Raphael Holinshed, and Thomas More. The Bard of Avon

was in fact incorporating the history of Richard's life, as he (and his audiences) knew it. It would be centuries before much of the 16th c. propaganda would be exploded. And yet there were enough eyewitnesses to Richard's conduct to confirm that he was indeed a ruthless man. The fifteenth and sixteenth-century accounts of his life, while they may be somewhat agendist, do contain many truthful details about his actions. And numerous record rolls still exist that, when analyzed, point to the fact that he was just as ambitious and grasping as any of his adversaries, or for that matter, as any of his relations and in-laws.

Still ... a happy marriage. Richard III. Who'd-a-thunk it?

Have you ever discovered that the truth about a specific event thoroughly contradicted what you [thought you] knew about it? Would you let the truth get in the way of a good story? How far would you go, as a writer? And as a reader, how much tinkering with the truth will you accept in your historical fiction if the plot, action, and characters are complex and compelling?