Whatever your family traditions, the Hoydens would like to wish you a happy holiday season. We'll be back in the new year with more history and more books!

Whatever your family traditions, the Hoydens would like to wish you a happy holiday season. We'll be back in the new year with more history and more books!

Monday, December 21, 2009

Happy Holidays!

Whatever your family traditions, the Hoydens would like to wish you a happy holiday season. We'll be back in the new year with more history and more books!

Whatever your family traditions, the Hoydens would like to wish you a happy holiday season. We'll be back in the new year with more history and more books!

Tuesday, December 15, 2009

Literary Cocktails, Jane Austen, and Discovering Characters

In November, I visited New York and had the great treat of staying with Lauren and sharing a wonderful evening of drinks and writer talk with Lauren and Leslie. That's the three of us to the left right at the appropriately named Bookmarks in the Library Hotel. Leslie wrote a great post about our evening on her blog. While discussing research methods, Richard III's marriage, and the vagaries of a writer's schedule, we sipped literary-themed cocktails (Leslie had the Dickens, which I think was brandy based, and Lauren and I both had the Hemingway, which had vodka, elderflower liqueur, and a float of sparkling wine).

I’m fortunate to have a lot of great friends, but there are some things that only fellow writers understand, particularly fellow writers who write in a similar area. Like all the Hoydens, Leslie, Lauren and I write historically set books. Even more specifically, Lauren and I both write books about espionage during the Napoleonic Wars. A few minutes after I walked through Lauren’s door, we were sitting on her sofa sipping wine and discussing the finer points of obscure Napoleonic intrigues, the challenges of writing books that cross genres, the delights and frustrations of primary source research, “what’s next” in both our series. We went on talking the whole trip, over brunches and dinners and cups of tea. We saw a riveting production of Hamlet with Jude Law and a great cast and talked about the Shakespearean references in both our books. We talked about Jane Austen, who plays a role in one of Lauren’s upcoming books, in light of the wonderful exhibit at the Morgan Library.

The exhibit was fabulous. I got chills looking at Austen’s letters, trying to decipher the words, noting that her handwriting was neater in the manuscript pages of Lady Susan than in the letters to her family, seeing first-hand the the crossed lines (turning the letter and writing crosswise to get the maximum use out of expensive paper) one reads about in Austen and other 19th centuries writers. There esearch gems such as a board game from 1809 called Journey Round the Metropolis: An Amusing and Instructive Game with pictures of London sights and an 1811 book called Ellen or the Naughty Girl Reclaimed with instructional stories for children illustrated by cut out figures. I think a rather prosy relative will present the book to young Jessica Fraser in one of my future novels. Jessica will enjoy playing with the cut outs but wrinkle her nose at the text.The exhibit also included a print of a portrait Austen said was Jane Bennet Bingley. I’ve always loved the letter of Austen’s in which she talks about attending an exhibition and finding a portrait of Mrs. Bingley. She adds that she looked for a portrait of Mrs. Darcy but didn’t find one, which she puts that down to Mr. Darcy not wanting to let go of any portraits of her. What I love about this letter, as I told Lauren, is that it shows Austen imagined her characters having a life outside the pages of her novels.

Which is just what Lauren and I were doing throughout my visit (including at a wonderful brunch at the Atlantic Grill in the picture below). Talking about our characters, their pasts, their interconnections, events we envisioned for them in the future. Questioning each other about spoilers for future books (fortunately neither of us minds knowing spoilers) and how various characters’ paths  might cross. Of course we both write series, which lend themselves to this sort of speculation, but I’ve always loved continuing the stories of books I read in my head after I turn the last page. I think it’s one reason that the books I write have always been interconnected.

might cross. Of course we both write series, which lend themselves to this sort of speculation, but I’ve always loved continuing the stories of books I read in my head after I turn the last page. I think it’s one reason that the books I write have always been interconnected.

I love the idea of Austen looking for her characters among the paintings at an exhibition. Much as today we look for our characters while watching a movie or turning the pages of a magazine. Such as when I watched the recent adaptation of Little Dorrit and thought Matthew MacFadyen would make a wonderful Charles. Or thinking how like Mélanie Eva Green was in Casino Royale. (Though neither of them was who I had in mind when I wrote Secrets of a Lady or Beneath a Silent Moon).

When I blogged about this on my own website, Susan commented, "I’ve certainly seen photos or paintings or actors who make me think of a character in a book: On reading Mary Balogh’s 'The Notorious Rake' I immediately pictured Daniel Day Lewis as Lord Edmond Waite. When I read 'Atonement', I thought Heath Ledger would make a perfect Robbie Turner. Much as I like James MacAvoy and think he’s totally adorable, he just doesn’t have the physical presence I thought Robbie should have. And I don’t see Michael MacFadyen as Charles. I like MacFadyen, but I think of Charles as having stronger features and coloring — an external expression of his passion and intelligence. Richard Armitage fits my image of Charles much better, but you are the author so you are certainly entitled to see whomever you like in the role."

Which goes to the fascinating idea of how the reader is a partner in the story and each reader reads a slightly different book. (Actually, having watched North & South several times while doing holiday preparations, I could definitely see Richard Armitage as Charles; of course it's hard to quarrel with Richard Armitage as just about anyone :-).

Monday, December 14, 2009

Maternity Clothes

For most of the Georgian era pregnancy itself doesn’t seem to be something that was celebrated or treated as something to be memorialized. The safe delivery of a child certainly was, and it is that, not the pregnancy, that tends to show up in letters and diaries. In contrast to the myth of pregnant women being “confined” alone and unseen, most reports show that they were out in public attending (and even hosting) events right up until the end.

There are few examples of clothes that were devoted specifically to maternity. There are several possibilities as to why this might be (and the truth is probably some combination of them al

l). Firstly, most images show that women simply wore their normal clothes, with editions such as aprons, shawls, and special waistcoats to cover the growing belly (the apron was so common a symbol of pregnancy that little girls playing dress-up would wear one when playing “house” and pretending to be pregnant). The fact that women’s skirts rode up in the front, or that things didn’t close fully doesn’t seem to have been of much concern. Secondly, if they did make special clothes, they probably altered them after, or passed them on to be worn by friends and family until they were worn out. Thirdly, they simply weren’t considered important enough to save.

l). Firstly, most images show that women simply wore their normal clothes, with editions such as aprons, shawls, and special waistcoats to cover the growing belly (the apron was so common a symbol of pregnancy that little girls playing dress-up would wear one when playing “house” and pretending to be pregnant). The fact that women’s skirts rode up in the front, or that things didn’t close fully doesn’t seem to have been of much concern. Secondly, if they did make special clothes, they probably altered them after, or passed them on to be worn by friends and family until they were worn out. Thirdly, they simply weren’t considered important enough to save.There are also descriptions of women wearing stays during their pregnancy, as well as an etching of a pattern for them (c. 1771).

For more information on pregnancy and early motherhood see “What Clothes Revel” by Linda Baumgarten. It has a whole section on this topic, complete with many excerpts from period diaries and letters.

Image, clockwise from the top right: An 18th century quilted gown laced over a matching waistcoat for pregnancy; The same gown as worn when not pregnant; A gown designed for a nursing mother, c. 1825-1830. The top panel lifts to expose an underbodice with slits; Detail from Diligence & Dissipation, c. 1796 The unwed pregnant woman is shown descending the stairs, her belly covered by an apron.

Friday, December 11, 2009

Little Men in Floppy Blue Pajamas

Have you ever taken a train through the High Sierras? Through mile-long tunnels and along tracks that cling to mountainsides overlooking deep canyons?

The most spectacular and dangerous routes were hacked out solid rock by hand by small (110 lb), tough, energetic Chinese laborers who hauled off the earth and rock in tiny loads and, as winter approached, worked 3-shift, 24-hour days and slept in tent cities at night.

Back in 1865 what were seen as those strange little men with their dishpan straw hats, pigtails, and floppy blue pajamas proved themselves the equal of burly Irish immigrants also hired to work on the railroads. At first, the railroad bosses judged the Chinese too frail and unmechanical for such work. [Had they known history, of course, they might have recognized the tremendous grit and cleverness of the Chinese, exhibited in the building of the Great Wall (also hacked by hand out of mountainsides) and the invention of clocks, gunpowder, paper, ceramic glaze, etc.]

The little Chinese men–actually farm boys from Canton–came to California originally to rework tailings of gold mines left by the ’49ers. Finally formed into railroad crews of from 12 to 20 men with their own cook and Chinese headman, the men proved quick to learn, slow to complain, and unfailingly punctual! (Irish workers were said to be a headache–promoting strikes, drinking up their earnings, and brawling.)

The Chinese amazed everyone: they didn’t strike; they didn’t get drunk; they bathed every day and drank boiled tea instead of the dirty water that sickened everyone else. They did gamble and occasionally had fights among themselves, but overall they were looked on as disciplined, efficient, reliable working machines. They were called Celestials. (The Irish were called Terrestrials.)

Clearing the path for the laying of railroad track encouraged competition among crews. Fifty-seven miles from Sacramento the Central Pacific Chinese crew ran into a shale mass in the flank of the Sierra, 200 feet above the gorge of the American River. Track would have to be laid along a ledge with no footholds, 1400 feet above the raging river below.

The Irish took one look and began protesting because it was so dangerous. The Chinese took over and triumphed. Lowered down the face of the cliffs in wicker baskets, the Chinese crews pounded holes in the rock, stuffed them with black powder, and set fuses. They were then hauled out of danger, and when the smoke cleared the hunks of rocky mountainsides had come tumbling down. The Chinese crews lost not a single man during this dangerous enterprise; they were paid $35 per month and that didn’t include food or lodging. They lived in on-site wind-whipped huts or dank caves and ate Chinese delicacies shipped from San Francisco and prepared by the Chinese camp cook.

Blizzards in the winter of 1866-67 all but stopped progress, but the Chinese continued to bore tunnels through solid rock, even though the men were often cut off by snow and had to eat stockpiled food while dodging avalanches. Tunnels were cut under the snow for access from lodging to work site.

The Great Track-Laying Race occurred after this bitter winter when both sides, the Union Pacific and the Central Pacific, were to connect in the desert. By this time, the Central Pacific crews included Irish men. For a time the Irish and the Chinese crews competed in clearing grading, with neither side warning the other of impending explosive blasts.

The Great Race between the Union Pacific and the Central Pacific began when each railroad owner wanted to beat the other to the connecting. Guess who won?

The Central Pacific’s combined Irish-Chinese crews managed to lay 10 miles of track in 12 hours and thus proved their superiority. The burly Irishmen would lug the iron track sections and drop them in position, and the Chinese would hammer them in place, by which time there would be another section of track waiting.

Thus was America built.

Source: The Railroaders [The Old West]; Time-Life Books, New York.

Wednesday, December 9, 2009

Law and Literature

In retrospect, that isn’t entirely true.

It isn’t just that I took terribly useful vocational classes at law school like Ancient Athenian Trials, on the theory that you never know when you might want to write a crime thriller set in Ancient Athens (apparently, there are still embarrassing pictures of me in Ancient Greek garb defending Eratosthenes floating around out there somewhere. Thank you, Harvard Law School Gazette). Law has all sorts of bearings on the world I write about and the characters I create, whether they realize it or not. The chance decision of a legislator or a judge can change the entire course of a character’s life—even when that decision takes place years before in a case that has nothing at all to do with that character.

It makes more sense than it sounds. My favorite example of this is Hardwicke’s Marriage Act of 1753.

You know all those novels where the lead couple is frantically dashing towards Gretna Greene? The entire elopement industry, in both fact and fiction, was spurred by this one piece of legislation, which decreed that the marriage of individuals under the age of twenty-one required parental consent, as well as that banns be published or a special license acquired in order for the marriage to be deemed valid. Marriages contracted in Scotland, which had its own set of laws, were not subject to these requirements, hence the mad dash for the nearest town across the border: Gretna Greene.

You know all those novels where the lead couple is frantically dashing towards Gretna Greene? The entire elopement industry, in both fact and fiction, was spurred by this one piece of legislation, which decreed that the marriage of individuals under the age of twenty-one required parental consent, as well as that banns be published or a special license acquired in order for the marriage to be deemed valid. Marriages contracted in Scotland, which had its own set of laws, were not subject to these requirements, hence the mad dash for the nearest town across the border: Gretna Greene. I’ve been thinking about this because the indirect consequences of impersonal legislation play a defining role in the lives of the characters in my latest book, The Betrayal of the Blood Lily, which is set in India in 1804.

Under the Governor-Generalship of Lord Cornwallis (yup, the same Lord Cornwallis who was forced to surrender to those pesky Colonials at a little place called Yorktown), laws were passed banning anyone with one Indian parent from serving in the East India Company’s army or civil service, the main source of income and advancement in British India. This meant that any offspring of an English father and Indian mother were banned, by birth, from most means of gainful employment. Only the more lowly trades remained open. James Skinner, later famous as Skinner of Skinner’s Horse, was apprenticed to a printer, from whom he ran away. Many took service as mercenaries in the armies of local rulers, a practice which exposed them to suspicion from both sides when war broke out between the British and the Mahratta Confederacy.

Under the Governor-Generalship of Lord Cornwallis (yup, the same Lord Cornwallis who was forced to surrender to those pesky Colonials at a little place called Yorktown), laws were passed banning anyone with one Indian parent from serving in the East India Company’s army or civil service, the main source of income and advancement in British India. This meant that any offspring of an English father and Indian mother were banned, by birth, from most means of gainful employment. Only the more lowly trades remained open. James Skinner, later famous as Skinner of Skinner’s Horse, was apprenticed to a printer, from whom he ran away. Many took service as mercenaries in the armies of local rulers, a practice which exposed them to suspicion from both sides when war broke out between the British and the Mahratta Confederacy. In The Betrayal of the Blood Lily, my hero, Alex (based loosely on a real life figure, his compatriot, James Kirkpatrick, Resident of Hyderabad), whose mother was Welsh, is reliant upon the Company for his livelihood, first as a captain in cavalry regiment, later as a member of the diplomatic corps. At the same time, his two half-brothers, product of his father’s liaisons with local ladies, are both banned from following in his footsteps, a source of deep conflict for Alex, who finds it difficult to serve and uphold an institution which excludes his family—although, for financial reasons, he has no choice but to do so. Cornwallis’ legislation, passed when Alex’s younger brothers were little more than toddlers, changed the whole course of his life and provides much of the backbone for the book.

So perhaps law has had an impact on my writing after all…. And if you’re looking for an attorney to defend an ancient Athenian, I’m your girl!

Friday, December 4, 2009

Bronte on the block

I am glad that Ms. Austen left no DNA behind.

Don't count on it. It seems that all the time possessions, papers and other artefacts come out of the woodwork as collections are sold or treasures unearthed in attics. How long before someone finds Jane Austen's hairbrush?

But today I'm cheering on the Bronte Parsonage Museum, because it's the day when Christies of NY is holding an auction of items from the William E. Self Library which includes a first edition of Wuthering Heights, owned by her sister Charlotte and with Charlotte's pencil notes for a second edition. The Museum naturally feels that the book, and the other Bronte items should be in the museum. I agree--I think it would be a tragedy if these items disappeared into the hands of a private collector--and I'm wishing them luck.

Also coming up this month, yet more Bronte items on sale through Sotheby's in London on December 17, when Charlotte's writing desk and Emily's drawing box will go on the block. (Photos courtesy of Sotheby's.)

Sotheby's is a fantastic research site, as well as a massive timesuck, by the way. The same auction also includes the only known letter from Byron to Stendhal, in which Byron defends the character of Sir Walter Scott:

I have known Walter Scott, long and well, and in occasional situations which call forth the real character - and I can assure you that his character is worthy of admiration, that of all men he is the most open, the most honourable - the most amiable...

The letter is dated May 29, 1823 when Byron was preparing to leave for Greece.

There's also a letter from Shelley regarding the publication of Frankenstein, in which he represents a "friend" who is not available to discuss the manuscript or terms of publication, written on August 22, 1817 when Shelley and Mary were living at Great Marlow in Buckinghamshire.

I know when I'm researching or blogging about historical items my first thought is that I'd love to own something like this. I'm hoping that the Bronte Museum has raised enough money to buy the books and furniture that surely belong there, because if they are bought by a private collector it's very unlikely any of us will ever see them.

Yet at the same time I understand the lure of owning something that was used by a known person, or a letter written by a favorite author.

What do you think? What would you like to own and what would you do with it? Donate it to a museum? Gloat over it, wearing cotton gloves, in the privacy of your own climate-controlled vault?

UPDATE: The results of the auction have been posted at BronteBlog. Not all bad news.

Thursday, December 3, 2009

Jane Austen and Galileo's fingers

The kind of history news I love--straight from the CNN headlines: "Galileo's Missing Fingers Found in Jar" and..."What Really Killed Jane Austen?"

Apparently, three fingers were cut from Galileo's hand on March 1737 and a tooth removed from his lower jaw, when his body was moved in Florence (removing body parts as relics from the sanctified dead was a common practice at the time).

The jar with two of the fingers and the tooth went missing in 1905, and only recently resurfaced when somebody brought them to a museum in Florence. The actual cause of Galileo's death remains to be determined...but at least now with fingers and a tooth, there is enough DNA to spare for testing--which could shed some light on the blindness that afflict Galileo late in his life and during his final illness. To read the whole article check out: http://www.cnn.com/2009/WORLD/europe/11/23/galileo.fingers/index.html

Today CNN posted: What Really Killed Jane Austen?

http://www.cnn.com/2009/SHOWBIZ/books/12/02/jane.austen.death/index.html

Now in almost every bio I've read or seen about here, the assumption was that she died of consumption, or tuberculosis...but apparently a doctor asserted in a paper he published (in 1964) that she died of Addison's disease (a failure of the adrenal glands). Katherine White, a social scientist who is a coordinator of the UK's Addison's Disease Self-Help Advisory Group says no way---Jane had none of the symptoms: headaches, sleepiness, slurred words, difficultly remembering words--that Jane Austen even wrote a comic poem to her sister 48 hrs before her death was proof she did not suffer from Addison's.

Without DNA, the retrospective diagnosis of Addison's disease (a condition barely recognized in Jane's lifetime) or lymphoma (another refuted cause of her death), will never be proven. Tuberculosis, which rampant in her time even amongst the middle class (milk was unpasteurized), is still the best guess.

Personally, I am glad that Ms. Austen left no DNA behind. We will really never know what killed her. Even the image of her posted here (a painting by Ozias Humphry, believed to be of Jane when she was about 14) is not a sure thing---but I'd prefer to have a mental image of her just like this.

Most of us I am sure, don't really need to know what really killed Jane Austen, or even Galileo. The work they left behind has given them immortality.

But the deaths of historical figures interest me, mostly because so many were premature or untimely. Have you ever researched the final hours of a famous historical figure?

Wednesday, December 2, 2009

Margaret & Peter: The Princess and the Equerry

By then Townsend’s marriage to Rosemary Pawle was headed for rocky shoals. In August 1950 he was promoted to Master of the Household, a permanent position requiring a one hundred percent commitment to King George.

Resigned to the inevitable, on October 31, 1955 Townsend declared, “Without dishonour, we have played out our destiny.”

Friday, November 27, 2009

Medieval Romance: On the Rise? Or Checking Out?

After a restful Thanksgiving Day, I spent today wandering through Barns and Noble and picked up the December issue of RT Book Reviews. One of the feature stories was written by my friend and fellow medieval writer Karin Tabke (check out page 24: Medievals---Are They In or Out?). Karin raises some interesting questions about medieval romance. This genre does not outsell the Regency time period according to Borders book buyer Sue Grimshaw, but editors at big houses (Harlequin for one) state that medievals are always in demand. They always have a place on those pie charts they show us about the stats regarding what in romance is selling (contemporaries are in the far lead).

I've been told many times "you'll never hit a list writing a medieval" and while I'd love to be a best-selling author someday, I'll always write medievals--- because I love them. I grew up reading Woodiwiss, Gellis, Beverly, Hunter, Deveraux, Garwood, Henley, and so many others---I can't imagine romance without them. I like the gritty, earthy medieval where heroines and heroes fight with each other and for their survival, or their kingdom's survival. The stakes were incredibly high and so many medieval romances mirror real-life history. Loyalty, love, betrayal, those years between 800 and 1500 have it all. Not that the other time periods don't---I love a good Regency or Western as much as anyone. I'm even working on a couple, but I will always have those days where I gotta "go medieval" at the keyboard.

Next week, my new release "Awakening His Lady" hits the electronic bookshelf (AHL is a novella published by Harlequin Historical UNDONE) and it's a medieval set in the 13th century. It won't be easy for medieval fans to find, but it's out there. You order it at: http://ebooks.eharlequin.com/B377409D-968B-4CA5-8B00-72DFF78B8D5A/10/126/en/ContentDetails.htm?ID=E2FDB2DF-7179-4BD0-B1D1-AAD1ADBDAE10 or just go to Amazon.com.

And hey, congrats to Lauren Willig, for a great review in RT (4 and a half stars!) for "The Betrayal of the Blood Lily"!

Monday, November 23, 2009

Happy November!

It's Thanksgiving week for those of us here in

November 1 All Saints' Day

November 2 All Souls' Day

Little distinction seems to have been made between the two days (which were also sometimes called Hallowmas; look familiar?). The celebrations included going "souling": wandering door to door for gifts of soul cakes or money and mugs of hot cider. The children even had a traditional song:

A soul-cake, a soul-cake

Have mercy on all Christian souls for a soul-cake.

The giving of the cakes was supposed to help the giver's soul, while the consumption was supposed to help those in purgatory (don't ask me how). This idea fell away with the Reformation, but bands of souling children making house calls continued . . .

November 5 Guy Fawkes Night

I'm sure many of you are at least passingly familiar with Guy Fawkes and his attempt to blow up Parliament in 1605. Bonfires rule the night, fireworks too. Often the pope was burnt in effigy (Fawkes being a Catholic), and anti-Catholic riots were not uncommon. In the northern counties, an oatmeal gingerbread called Parkin was baked and given out (recipes dating as far back as 1800 can be found).

November 11

I love specific local customs! In Fenny Stratford, starting in 1724, an annual sermon is read in memory of a local squire. At the end, six small cannons are fired off, at noon, 2PM and 4PM.

November 13 St. Brice's Day

More local customs: this Saint's Day is celebrated in

November 17 Queen Elizabeth Day

Sermons, bonfires and ringing bells. So popular was this day that Charles I felt it overshadowed the celebrations for his own birthday!

November 30

More fun local customs: In Buckinghamshire and Northhamptonshire they celebrated by going out into the woods to kill squirrels, though mostly the hunt was an excuse to wander about, make merry, and be as loud as possible.

Also on St. Andrew’s Day (from 1766 on) is the famous Wall Game at

Any strange local holidays or festivals where you live?

Friday, November 20, 2009

Remember Frank Yerby?

Don’t laugh, but I’ve been reading Frank Yerby! To be specific, An Odor of Sanctity. Published in 1965(!) it’s another oldie and I selected it for a very particular reason. The story is set in 9th Century Spain, when society was a rich mixture of Muslims, Arabized Christians known as Mozarabs, and Jews, and I have long loved this era and this place.

When I was in high school, Frank Yerby was “the” racy author we were forbidden to read. I remember that the Watsonville librarian kept Yerby’s books on the top shelf behind her desk, and one could check them out only with a written note from a parent.

That didn’t stop our salacious fascination with the Yerby novels; chief among them were The Foxes of Harrow. Such works titillated our guilty pleasure well into the ‘60s, at which time I grew up and went off to college and read Shakespeare.

If life moves in cycles (circles?), my fiction reading through the years has arced back to where I started, with Frank Yerby. However, I’m older now and an author myself, and I honed in on Yerby because it turns out he was an accepted historical expert on medieval Spain!

Aside: The very first book I ever wrote, for which I did mucho research, was also set in medieval Spain. That book never sold (though, after reading the historical lore on marriage customs that Yerby dug up, I think there still might be a chance); the sequel, with a similar setting, was published in 2008 (Templar Knight, Forbidden Bride.

But back to Yerby. The sense of place in Cordoba and Toledo, and the incredible level of detail, right down to how the slave girls smelled and the slow Mozarabization of the hero’s garments and undergarments over the years, the spices, the skin colors, the perfumes... all of it was delicious.

The story is basically a “coming of age” tale about a young “Gothic” (French) man and his picaresque adventures, his involvements with women, his love affairs, and his struggle over questions of faith. We follow Alaric from his 14th year to the end of his life, watch his inner conflicts between sensuality and mysticism, and agonize, as he did, over the incipient erosion of paradise, as Muslim Spain was regarded.

Yerby’s writing style is fascinating: it’s dated, yes, with overlong, wordy sentences and a romanticized view of women (at least until Alaric is grown). Here is an example:*

“She sat there listening to the night noises, and feeling her nerves crawling just beneath the surface of her skin. It had not been so bad at first, because her former master had been with her then. But some two hours agone that great grizzled lion of a man whom Alaric had called Father had come into the room without a knock or a by-your-leave, and stood there eyeing her up and down as though she were some rare and distinctly unpleasant beast.”

In my view, this is one of those works whose content rises above its presentation. The struggles of a rational man in an irrational world speaks to us even today.

Next on my list is Yerby’s The Saracen Blade, published in 1952. I can hardly wait...

*Frank Yerby, An Odor of Sanctity, Dial Press, New York, 1965.

Friday, November 13, 2009

Love Stories: An Anniversary Post

My original intent in this post was to write about the thrilling week I've just spent discovering what for me might be the best book ever on writing and being a writer: About Writing: Seven Essays,Four Letters, and Five Interviews, by the noted science fiction and literary writer, critic, and teacher, Samuel R. Delany.

But it seems I'm going to be taking a leisurely, personal, even sentimental route to get to it. Because as a romance writer who's recently celebrated my fortieth wedding anniversary, I figure I'm entitled to say it by way of a little love story.

And as a romance writer who's also a literary theory groupie, I'm gonna begin that story with some thoughts about the romance genre, my best understanding of which comes from my mother, a fiercely energetic reader of mostly midlist literary fiction and mysteries.

A stalwart fan of my writing, Mom wasn't thrilled when I was about to be published in romance. (While as for my erotic, Molly Weatherfield books -- take it from me, there are certain things most of us will not want to share with close family members.) But in a brilliant flash of female and readerly intuition, she nonetheless gave me the most helpful overview of the field I was entering that I'd ever heard (and have yet to hear better, after years of podium speeches at rubber chicken romance writer luncheons).

"Well," she said, "I can understand the appeal of it. Because, after all, the most important story in my life has to have been the love story of how I met and married your dad."

Most important story in her life. What does it mean to have a story in your life? We might have many, but my guess is that for lots of us the love story might be the most important -- or at least the one most easily understood and valued as a story.

Because courtship (at least when it's successful) always seems to fall into narrative form, with irony, complications, surprises, artful turns, missed connections, and near total disasters before it all gets worked out (or before it becomes the work of having a life together).

I've heard romance writers say our genre is so popular because life is so difficult without stories. And while this might be true, to me it comes awfully close to saying that many women's lives are so awful that they need romance to compensate.

I'd put it differently. I think that part of being a woman at this time in human history is having that romance story at your core even if you don't read the romance novels. And even if (even better perhaps, if) you have a richness of other resources and activities in your life.

Because so much of adult life isn't -- nor should be -- story. Romance fiction, I think, is written in counterpoint to the tough, necessary, workaday, not-so-awful but awfully routine, redundant, and non-narrative parts of life. To remind us of how it feels to be at the center, to be heroine of an honest-to-God thrilling story. Thereby bringing us closer to the story we each carry around at our center.

The question is, I suppose, how you like your stories. Me being a nerdy sort, I like them slightly off center (and thanks again, Dear Author bloggers, for noticing).

Some of my favorite stories -- and favorite love stories -- are the edgy, marginal ones, hidden in plain sight like the lady's intriguing missive in Poe's "The Purloined Letter." It's one of the ways that the romance and mystery genres share... well, a genealogy, if you like. And it's why one of my favorite romances in fiction -- between Jane Fairfax and Frank Churchill in Jane Austen's Emma -- is one that's hidden in plain sight among the workings of the main protagonists' romance plot (and why Emma reads rather like an ancestor of a country house detective novel).

Bringing me at last to how I found what I think is the best how-to-write book ever.

Or at least to the romantically hidden-in-plain-sight way it was recommended to me, some years ago, by my husband Michael, at a reading at the bookstore he and I were part-owners of for many years.

The reader was -- to get back to the original subject of this post -- Samuel Delany, the brilliant and (as Michael aptly put it in his introduction), "the nicest titan of contemporary letters you will ever meet." It was certainly the nicest bookstore event in my memory -- a long, generous, intimate-feeling reading, q&a, and discussion -- and the hundred or so fans and friends who'd gathered seemed to think so too.

But the most important part of the evening for me, though I didn't know it at the time, was another part of Michael's introduction, where he said that if anyone needed one short piece of writing instruction, one couldn't do better than the essay "Of Doubts and Dreams," reprinted as an afterward to the book we'd come together to celebrate, Aye, and Gomorrah, a collection of Delany's short fiction.

I was very busy at the time -- working fulltime at my then day job as a computer programmer after waking up at 4 to make my deadline for rewrites on my first contracted romance novels. And so I didn't even consider checking out the essay until sometime after I submitted the rewritten version to my publisher, when I picked up the copy of Aye, and Gomorrah that was still floating around our bookshelves. (I love the physicality of books, how sometimes they to fall into your hands when you need them most. Someday I suppose I'll get an e-reader. Someday.)

Anyway, I opened to "Of Doubts and Dreams," read it through with profit and delight and... a dawning suspicion.

"You were addressing that comment to me, weren't you?" I asked Michael. "About what a terrific resource that Delany essay is?"

He nodded. "You were so busy," he said. "I didn't want to pressure you. But I knew you'd be able to use it."

Perhaps it's not one of those scenes in a Regency where the host suddenly raises his glass of champagne to declare his love, transforming a shy mouse of a girl into the toast of Mayfair with all the ton in attendance and applauding.

But it worked for me and still does. A little love story, hidden in plain view amid the everyday crush of working life.

While as for the "Of Doubts and Dreams" itself, more recently collected in the (for me) indispensible About Writing, let me, in the time and space I have left, introduce you to two of its points.

The first ought to be familiar to writers of historical fiction, though it's not surprising to hear it from a science fiction writer. Delany says he "filched" it from another science fiction writer, Theodore Sturgeon (and I'm not sure which of the words are Sturgeon's and which are Delany's). But for me it's news that stays news and maybe it'll help someone else out there as well:

To write an immediate and vivid scene... visualize everything about it as thoroughly as you can, from the dime-sized price sticker still on the brass switch plate, to the thumbprint on the clear pane in the unpainted wooden frame, to the trowel marks sweeping the ceiling's white, white plaster, and all in between. Then, do not describe it. Rather, mention only those aspects that impinge on your character's consciousness.... The scene the reader envisions... will not be the same as yours -- but it will be as vivid, detailed, coherent, and important for the reader as yours was for you.

Modestly, Delany sums this up as "don't overwrite." But perhaps from the bit I quoted you can imagine much he subsumes under each of the simple points that constitute this essay: don't overwrite, avoid thinness, and don't indulge cliche.

And perhaps you can see what an important thing his points add up to. Which is that there's a moment of writerly doubt that's the right moment of doubt, when you sense clutter or thinness or cliche. That writing happens at that moment when you make a choice to work to correct the clutter or thinness or cliche -- because it's those things that steer you away from the story you're really telling.

Which would be a terrible thing to do to the story at the center of a reader's life.

Your turn. Writers, tell me about what books or what advice has helped in your writing. (I notice it's National Novel Writing Month, where we're advised to put aside our doubts and hesitations -- does that approach work for any of you?)

And anybody who wants to share the shape of a love story -- please feel free.

Wednesday, November 11, 2009

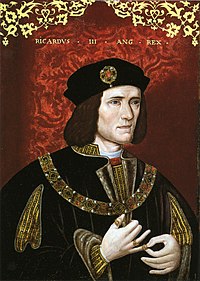

Richard III & Anne Neville: a love story ??

I never noticed that this portrait does show one shoulder slightly higher than the other ... but I believe it's the wrong shoulder!

I don't know about you, but my introduction to Richard III and the Wars of the Roses, perpetuated for decades by the feuding dynasties of Lancaster and York, was through William Shakespeare. I was in high school at the time, and it would be years before I learned that the man rarely let the truth get in the way of a good story.

Now that historical research is part of my bailiwick, I'm having great fun re-reading Shakespeare's history plays and separating the factual details from the fanciful ones.

As I've been delving into Richard's life for my third work of historical nonfiction, currently titled ROYAL PAINS: A Rogues' Gallery of Brats, Bastards, and Bad Seeds, I thought it would be fun to revisit Shakespeare's text after having a "eureka!" moment during my research into Richard's actual, factual, life.

Richard had a happy marriage.

Who knew?

Consequently, Richard and Anne Neville didn't make it into my post some months ago about happy marriages in Shakespeare; but today they get their due.

And by the way, Richard was also not born with a crookback, or a withered arm. Or a full set of teeth, or shoulder-length hair. Nor did he gestate in his mother's womb for two years. These physical descriptions are the products of Tudor-era propaganda, most of which no rational person, at least in our day, would credit. And yet -- the humpback, and even the useless arm, have stuck with us, providing the image of a Yorkist Bob Dole (yes, I know Dole isn't hunchbacked). The truth appears to be that Richard had one shoulder (the left one) that was slightly higher than the other, and that he was frail and slight as a boy, in stark contrast to his handsome brother George, Duke of Clarence, who was a charismatic jock-type, or his 6' 4" oldest brother, Edward IV, a ladykiller, bon vivant and fashionisto until job security after 1471 turned him into a louche and lascivious gourmand and womanizer.

Richard did indeed have to push himself to overcome his frailness as a boy in order to excel in the usual manly pursuits of the era from martial skills to horsemanship, falconry, riding, and dancing. He did in fact know how to "caper nimbly in a lady's chamber to the lascivious pleasing of a lute."

But back to Richard's marriage.

In Act I sc. ii of Shakespeare's Richard III, our protagonist, then Richard Duke of Gloucester, woos the widowed Anne Neville in exceedingly reptilian fashion. The encounter takes place on a London street in the middle of a funeral cortege. Anne was the younger daughter of Richard Neville, 16th Earl of Warwick, known as "the kingmaker" for his Karl Rove-like strategic (and martial) talents in securing England's throne for the Yorkist usurper Edward IV, then backing the man Edward had deposed, the Lancastrian Henry VI. Anne's older sister Isabel had, against the wishes of King Edward IV, married George, Duke of Clarence, brother of Edward IV and Richard, Duke of Gloucester.

Anne Neville's father, Richard Neville, 16th Earl of Warwick, known as "the kingmaker" -- hardly a St. Francis-type. This drawing is from a chronicle of the time known as the Rous Roll.

In Shakespeare's wooing scene, Anne has recently lost her husband, Prince Edward (the former Prince of Wales), son of the deposed (and subsequently assassinated) Henry VI. Edward fell in the battle of Tewksbury on May 14, 1471, which decimated the Lancastrian forces, ushering in years of Yorkist supremacy.

Throughout Richard III, the late Prince Edward is described as noble and virtuous. The real Edward of Lancaster was an arrogant 16-year-old jerk. He and Anne (b. June 11, 1456), who married him on December 13 1470 at the age of 14, had a purely dynastic marriage. And, contrary to Shakespeare's text, Richard (b. Oct. 2, 1452) did not personally stab him to death; During the battle Edward was in fact set upon in a melee. The identity of the man who delivered the fatal thrust remains unknown .

In their famous scene in Richard III, Anne is not lost for epithets to sling at her pursuer: "fiend," "dreadful minister of hell," "foul devil," "defused infection of a man," "devilish slave," "hedgehog," and "homicide." I think "defused infection of a man" is my personal favorite, though "hedgehog" comes in a close second. Richard's heraldic device was the boar, so maybe this is one of the ultimate inside jokes, a deliberately bitchy twisting that reduces a noble, if overbearing, creature to a woodland nuisance.

Here's a sample of Shakespeare's version of this highly unusual -- and exceedingly swift -- courtship:

GLOUCESTER: He that bereft thee, lady, of thy husband,

Did it to help thee to a better husband.

LADY ANNE: His better doth not breathe upon the earth.

GLOUCESTER: He lives that loves thee better than he could.

LADY ANNE: Name him.

GLOUCESTER: Plantagenet.

LADY ANNE: Why, that was he.

GLOUCESTER: The selfsame name, but one of better nature.

LADY ANNE: Where is he?

GLOUCESTER Here.

[She spitteth at him]

Why dost thou spit at me?

LADY ANNE: Would it were mortal poison, for thy sake!

GLOUCESTER: Never came poison from so sweet a place.

LADY ANNE: Never hung poison on a fouler toad.Out of my sight! thou dost infect my eyes.

GLOUCESTER: Thine eyes, sweet lady, have infected mine.

LADY ANNE: Would they were basilisks, to strike thee dead!

This spirited sparring comes from one of the finest, and most famous, scenes in Shakespeare's canon, and I can attest that it is also one of most fun to perform -- but it is pure fantasy.

England was more or less embroiled in civil war when Richard was a boy, thanks to the perpetually warring factions of Lancaster and York. He was sent out of harm's way to lodge with Warwick's family at Middleham, the earl's Yorkshire estate. Richard and Anne were childhood playmates, and as such, were always fond of each other.

In 1470, the reign of Richard's older brother Edward IV was being challenged by a conspiracy to reinstate Henry VI, fomented by none other than their own brother the Duke of Clarence (who had the dim and addlepated notion that he would eventually be crowned) and the Earl of Warwick, Clarence's father-in-law, and the pestilence in his ear.

Richard, still in his late teens, headed to command and secure the north for his brother Edward, but before departing he requested, and was granted, permission to wed Lady Anne Neville. When he returned from the north to claim his bride, he discovered that Clarence, husband of Anne's sister Isabel Neville had decided that Anne was his ward (Warwick having been killed at the Battle of Barnet on Easter Sunday). Clarence intended to claim Anne's portion of her inheritance for himself and Isabel and therefore had no desire to see her wed, even to his own kid brother.

In fact, it is Clarence who is the villain of this particular portion of the story. He disingenuously insisted to a confused and angry Richard that Anne was not in his household. After an exhaustive search, Richard found his betrothed in London disguised as a kitchen maid in the home of one of Clarence's friends. Like a true romantic hero, he rescued her and brought her to sanctuary at St. Martin le Grand, thereby shielding her from any efforts by Clarence and his adherents to nab or harm her. He assured Anne that there were no strings attached to his chivalry; his action in no way obligated her to go ahead with their marriage.

Insisting that he was the girl's guardian following the death of her father, Clarence ultimately consented to permit Richard to wed Anne on the condition that Richard inherit none of her estates.

Anne and Richard were cousins; in order to legally wed they required a papal dispensation overlooking their consanguinity. But having finally secured permission from his family to marry Anne, Richard was too impatient to wait for the Pope's paperwork to arrive. Instead, on May 14, 1472, political expedience being as pressing as passion, he claimed his beloved from St. Martin le Grand and they were wed on the spot. The bride was one month shy of her 16th birthday. The groom was 19 (and he'd already fathered two children by then; I don't know the mother[s]' name[s].)

When was the last time you saw a production of Richard III where the characters were played by actors young enough to look like teenagers?! I'm betting never.The couple --who were genuinely in love, at least according to Richard's eminent twentieth-century biographer Paul Murray Kendall -- immediately set off for Wensleydale castle, far from any of their grasping relatives. They had only one child, a son named Edward born in 1473, whose health was always delicate and often prevented him from traveling with his parents. He was invested as Prince of Wales on September 8, 1483, but he died during the spring of 1484 at the age of 11. Richard and Anne were inconsolable, and it was said that the boy's death hastened her own demise.

Unlike Shakespeare's plot, in which Richard is ultimately suspected of poisoning Anne in order to wed his niece, Elizabeth of York, Anne developed consumption, the same disease that killed her older sister Isabel. Wasting away from grief and illness, she died on March 16, 1485, a little more than five months before Richard met the sharp end of a sword at Bosworth Field on August 22.

Richard still remains an enigma to us, a product of the violence of his times; a loyal brother and talented administrator, but unquestionably he had blood on his hands. In Shakespeare's "defense," he based his history play on the Tudor-era writing of chroniclers Edward Hall, Raphael Holinshed, and Thomas More. The Bard of Avon was in fact incorporating the history of Richard's life, as he (and his audiences) knew it. It would be centuries before much of the 16th c. propaganda would be exploded. And yet there were enough eyewitnesses to Richard's conduct to confirm that he was indeed a ruthless man. The fifteenth and sixteenth-century accounts of his life, while they may be somewhat agendist, do contain many truthful details about his actions. And numerous record rolls still exist that, when analyzed, point to the fact that he was just as ambitious and grasping as any of his adversaries, or for that matter, as any of his relations and in-laws.Still ... a happy marriage. Richard III. Who'd-a-thunk it?

Have you ever discovered that the truth about a specific event thoroughly contradicted what you [thought you] knew about it? Would you let the truth get in the way of a good story? How far would you go, as a writer? And as a reader, how much tinkering with the truth will you accept in your historical fiction if the plot, action, and characters are complex and compelling?

Sunday, November 8, 2009

Can the Snood Save Christmas?

What a surprise---I checked out The Wall Street Journal Yesterday to see the headline in the style section: Can the Snood Save Christmas?

Really????? The SNOOD?

Now as a medieval writer, the snood conjures something entirely different from what was shown in the style section. I was more than surprised to see the tube-like scarf I used to wear on the ski slopes take a new form into this massive, blanket-like head-scarf…a hot fashion item, according the Journal, that designers are determined to foist upon us during the economic down-turn, because it represents an apparel item that is new, that we don’t already have.

Naturally, the History Hoyden in me drove me to do to a little research about snoods:

From the all web-encompasing summary source, Wikepedia: A snood is a type of headgear, historically worn by women over their long hair. In the most common form it resembles a close-fitting hood worn over the back of the head. The band covers the forehead or crown of the head, goes behind the ears and under the nape of the neck. A sack of sorts dangles from this band, covering and containing the fall of long hair gathered at the back of the head. A snood is sometimes made of solid cloth, but sometimes of loosely knitted yarn, or other net-like material---now this, as a historical writer, is what I call a snood.

More: “The word is first recorded in Old English from around 725 and was widely used in the Middle Ages for a variety of cloth or net head coverings, including what we would today call hairbands and cauls, as well as versions similar to a modern net snood. Snoods continued in use in later periods especially for women working or at home.

In Scotland and parts of the North of England a silken ribbon about an inch wide called a snood was worn specifically by unmarried women as an indicator of their status until the late 19th or early 20th century [1]. It was usually braided into the hair.

Snoods came back into fashion in the 1860s, though the term "snood" remained a European name, and Americans called the item simply a "hairnet" until some time after they went out of fashion in the 1870s. These hairnets were frequently made of very fine material to match the wearer's natural hair color (see 1860s in fashion - hairstyles and headgear) and worn over styled hair. Consequently, they were very different from the snoods of the 1940s.

Snoods became popular again in Europe during World War II. At that time, the British government had placed strict rations on the amount of material that could be used in clothing. While headgear was not rationed, snoods were favored, along with turbans and headscarves, in order to show one's commitment to the war effort.

Today women's snoods are commonly worn by married Orthodox Jewish women, according to the religious custom of hair covering.”

And with regards to The Wall Street Journal’s fashion commentary, I think below explains it all very nicely:

“The word has also come to be applied to a tubular neck protector or warmer, often worn by skiers or motorcyclists. The garment can be worn either pulled down around the neck like a scarf, or pulled up over the hair and lower face, like a hood. A commercial company making women's clothing also uses the word as a trademark and sells a decorative variant of the sports snood as its signature product.”

Retailers today are apparently trying to give the snood a new name (have to admit, it’s a fun word to say)---they want to call it the “infinity scarf, or infinity loop”---not so fun, IMO.

At any rate, I still prefer the historical and traditional version of the snood---the lovely hairnet, oft adorned with pearls or beads, used to capture the cascading tresses belonging to the ladies centuries past.

Will the snood, in any variety, save the Holiday Season of 2009? One can only hope. I think there is something romantic in general about a lady covering her head or capturing her hair.

Have any of you ever worn the modern or the historical version of the snood?

Wednesday, November 4, 2009

The Influence of Dorothy Sayers and Peter & Harriet

The great discussion following my recent blog on The Scarlet Pimpernel inspired me blog about another series of books that have had a huge influence on me as a writer and on my Charles & Mélanie books in particular. Dorothy Sayers’s Lord Peter Wimsey series, particularly the books featuring Peter and Harriet Vane.

My mom introduced me to British “Golden Age” (twenties and thirties) mysteries when I was a teenager. They became some of my favorite books. In particular, those with an ongoing love story/marriage that unfolded across various books–Margery Allingham’s Albert Campion and Amanda Fitton, Ngaio Marsh’s Roderick Alleyn and Agatha Troy, and above all Dorothy Sayers’s Peter Wimsey and Harriet Vane. Typically for me, I read the books completey out of order. I started with Have His Carcase, the second of the four full books featuring Harriet which Sayers wrote (there have since been two continuations written by Jill Paton Walsh). I knew they ended up together, but I so wanted to read more. It was a Sunday, so the library wasn’t open. I still remember how sweet my father was, driving me to a bookstore that day where the only book I could find was the fourth, Busman’s Honeymoon. Then I read Strong Poison, where Peter and Harriet meet (Harriet is on trial for murdering her lover), and finally Gaudy Night.

There’s so much I love in these books. The finely drawn characterization. The interplay between the mysteries and the developing love story stretched out over multiple books. The nuanced look at the development of a relationship (which doesn’t stop evolving with marriage). The difficulties, particularly for a woman, of maintaining your own identity in a relationship. The risk of trusting and letting down emotional barriers. The wit and passion of the two main characters. The emotions which are all the more intense for being kept in careful restraint for so long. Strong Poison starts sets up Peter and Harriet and their emotional conflict perfectly. Have His Carcase is a wonderfully intricate mystery (probably my favorite of the four as a mystery) while at the same time revealing more layers to both Peter and Harriet and moving the relationship along. Gaudy Night is one of my all time favorite love stories. Purely as a mystery it’s not my favorite, but the thematic interplay of the mystery and the love story is brilliant and the character development is fascinating. Busman’s Honeymoon is a wonderful look at a developing marriage, by turns funny, wrenching, and heart-stoppingly romantic, and also a great study of the darker side of investigating a murder and proving someone guilty.

I’ve always loved romantic detective partnerships. And I find they offer wonderful scope for developing a story. The twists and turns of the mystery can echo the twists and turns of the relationship, the theme of the mystery can echo the theme of the issues the hero and heroine are confronting. The same elements that have me rereading the Peter and Harriet books have me rewatching episodes of The X-Files to analyze Mulder and Scully’s evolving relationship.

Of course Dorothy Sayers has been a huge influence on me as a writer. There’s a code-breaking scene in Secrets of a Lady that’s an homage to the wonderful code-breaking scene in Have His Carcase. And I started Beneath a Silent Moon with an image of the final scene between Charles and Mélanie, which was inspired by the final scene between Peter and Harriet in Busman’s Honeymoon.Who else is a Sayers fan? (I know Lauren is, because we've talked about the books.) Writers, what books that particularly inspired you as a writer? Readers, what books have helped form your reading habits? And am I the only one who reads series hopelessly out of order?